Writing in Circles to Find True North

Trading comfort and control for something more beautiful

First, I want to welcome the little flurry of new subscribers who found their way here by way of a Note I shared recently, about writing the big things small.

What a fun thing it has been to connect with fellow writers who are captivated by this question—of how we might write about things that feel too big too contain, by finding meaning and resonance in the granular.

Welcome! I'm so grateful you're here.

My husband and I have an unspoken rule that on days this nice, when the sun is out and daffodils spring from earth across the neighborhood, it is criminal not to get outside for a walk. We grab our water bottles and head to the large wooded park down the road, pull into the first parking lot and arbitrarily choose a trail.

Gradually we veer further away from pavement and into the trees, still bare from winter. I'm happy to let him lead, his inner compass has always been better-calibrated than mine. At each fork I chuckle and announce that if I were alone, I'd have to turn back and retrace my footsteps through the muddy leaves if I had a prayer of finding the car again.

"You'd find your way," he replies. "These trails all loop back around eventually."

• • •

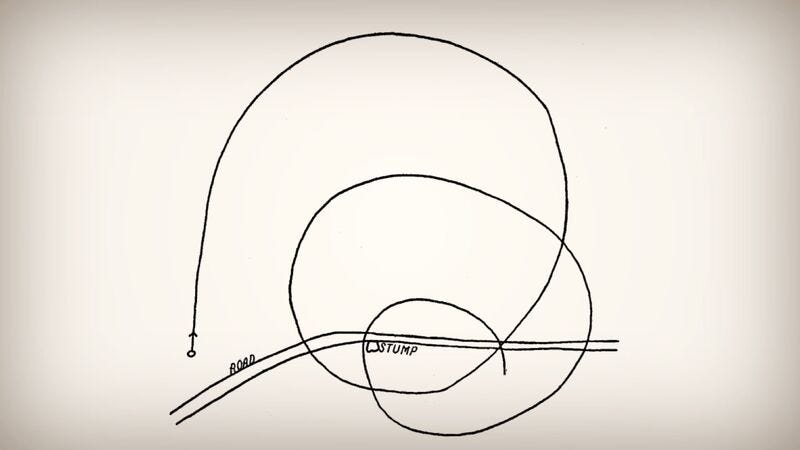

In the 1920s a young biologist named Asa Schaeffer brought his friend to the edge of a country field, put him in a blindfold, and asked him to do his best to walk in a straight line.1

The friend stayed on course at first before tilting off to one side, eventually looping back around to create a series of overlapping not-quite-circles. Schaeffer purportedly repeated this same test with swimmers, rowers, even automobile drivers. Each time, the blindfolded traveler slipped into circles and created something resembling a spiral pattern.

For as long as I can remember I’ve been the kind of person who likes straight lines, set plans, clear expectations. My writing brain, though, is a different animal. It pounces, zig-zags, chases its tail. Even when I sit down planning to write something singular and linear, it has a way of sprouting legs and skittering across the page, refusing to be caught.

So when I first learned about braided essays and their meandering structure, I thought, well this could be fun.

I bought a course from Lilly Dancyger on writing the braided essay and devoured her process. Per her instructions, I began by making lists of possible writing topics and looking for connections between them. Right away I clocked the thematic harmony between three of my topics: Yosemite, my grandmother, and my anxieties about aging.

If I squinted, a path forward came into focus. I would bring together stories of my grandmother with my own worries around becoming fragile as I get older, using Yosemite as a natural foil.

I would research the thrill-seekers who flock to Yosemite—the rock climbers, backcountry backpackers, white water rafters. I'd write about Grandma’s time in the Sierra Club and the time my Dad backpacked from Mammoth to Yosemite for his 40th birthday, how they both challenged themselves and chased adventure at ages older than I am now. I’d try to name that thing they all must have, that I don't. Find a way to turn all their stories into some sort of inspirational mandate to keep pushing myself physically as I get older.

Instead, researching Yosemite pulled me in unexpected, confusing directions. Facts about conservationists, ancient glaciers and towering sequoias tugged at my attention, pulling me further and further off course.

The more I drifted from the path I imagined this essay would take, the less faith I had in where I was going or where I'd end up.

• • •

In 2007 nearly a century after Asa Schaeffer’s field test, the German scientist Jan Souman set out to formally test the theory that a lost traveler will wind up walking in circles.

He conducted experiments with blindfolded volunteers outfitted with GPS trackers in open fields, and set non-blindfolded participants loose in unfamiliar terrain—both the Tunisian desert and the Bienwald forest in Germany. Consistently, Souman found that without a strong visual reference point like the sun or the moon, lost travelers will meander, loop, even criss-cross their own path.

I couldn’t see it then, but the only way I was ever going to write an essay worth writing was to get completely turned around. I’d have to lose the trail, along with my conception of where it was taking me.

Of course, that didn’t make the writing process any less painful. Each time I returned to my slew of open browser tabs to try and write my way through the confusion, I edged closer to throwing my laptop out the window. I felt confronted by my low tolerance for uncertainty and mediocre drafts, unable to see where any of it was leading or how it would come together to say something coherent. I spiraled, convinced I’d never find my way out of the woods.

Over the years scientists have posited all kinds of explanations for this circling tendency. Some thought it must have to do with a person's dominant hand or which side of the brain they favored. Others believed having one arm or leg that's slightly longer than the other must be the cause. Souman and his team tested these theories, unable to find a correlation.

Instead, Souman believes the answer stems from tiny errors in the part of the brain that processes sensory input and coordinates movement. Without visual cues in our environment, he says, those errors distort our internal sense of 'straight ahead.'

It wasn’t until I made peace with the dark that I could hear the essay telling me where it wanted to go, how it wanted to unfold. Unplanned rabbit holes and zigzags off-course became their own kind of compass, leading me somewhere much truer and more urgent than my original destination.

By the time I finished the essay, it had become so much more than a pat reminder to take more risks or embrace my outdoorsiness. Writing that piece pushed me into new territory, defied me to find a way to square my hunger for known quantities and creature comfort with my desire to conserve whatever wildness is in me. To ask: what is the hidden price of an always-comfortable orientation?

writes about the thrill of sending herself out on assignment for her Woman in the World essays, a way to challenge the shyness she's known since childhood. "This will always be the joy of writing," she says. "A chance to inhabit a different trajectory, to sketch, freehand a different fate for yourself."

I read essays from my favorite writers here on Substack who write about their time backpacking through coastal sagebrush, camping in the Colorado mountains, sleeping in truck beds under the stars beside their partner and some part of me aches—with envy or embarrassment, I'm not sure.

Why not me? the same part asks. What will it take for me to inhabit a different trajectory? To trade comfort and control for something more beautiful?

• • •

The word bewilderment has German roots, stemming from the archaic word wilder meaning "to lead astray or lure into the wilds." Today it refers to a complicated or confusing state or condition—as in, a bewildering tangle or confusion.

I wonder if building up a tolerance for getting tangled on the page might be a gateway into living a braver, wilder kind of life I quietly imagine. If straying from the safety of 'straight ahead' is how we find our way into something wild and new, that still somehow feels like true north.

In his 1897 paper, Norwegian biologist F. O. Guldberg argued circling was not a deviation, but a law of nature.

Just as schools of fish will swirl in divers' headlamp glow and foxes will move in circles to confuse hunters, Guldberg argued circular movement is an animal instinct that guides us back somewhere safe and familiar—“the native place to which animals in the struggle for existence must so often return, be it the udder of the cow, the warmth-giving wings and the guiding experience of the hen, or the sheltering tree or bush chosen by maternal instinct.”

We circle so we might find our footing.

The insights and meaning that emerged from writing that Yosemite piece have pressed themselves into my heart and mind. I cannot shake them, even if I wanted to.

That essay became the reason I chose 'wild' as my word of the year for 2025; it gave me a new way of understanding myself, and a new vocabulary for how I want to approach my relationship to aging, discomfort, adventure. Writing it would not have been possible without a blindfold and a willingness to walk headlong into mystery.

To this day, there appears to be no clear consensus explanation for the human tendency to circle when we are lost. Maybe it’s the not-knowing that keeps scientists coming back.

I know now the essays that force me to lose my way so that I might emerge transformed are the ones I'm most interested in writing.

As much as it may gnarl my stomach and stoke my fear, anytime I sit down to write I remind myself: The kind of uncertainty that rattles me most just might be the thing that brings me home. The more desperately I want a map, the more I know I’m writing something worthwhile.

The Webs We Weave is a place for meaning-makers, featuring essays that weave lived experience with fascinations and sharp-toothed questions as I tangle with what kind of woman I want to be. Thank you for being here.

Sources referenced for this piece include: “Why We Walk in Circles” by Greg Miller, via Science.org; “A Mystery: Why Can't We Walk Straight?” by Robert Krulwich, via NPR; “The Dread and Bewilderment of Walking in Circles” by Rober Moor, via The New Yorker; and “Do lost people really go round in circles?” by Ed Yong, via National Geographic

MICHELLE! Another banger of an essay. So, I have been doing research on moths. They circle lights and lamp posts and candles because they use moonlight in nature as their reference point. So, when not out in the physical world with moonlight as a guide, they start circling whatever light source they find and they go in literal circles. I found that so poignant. In order to be found, they must get lost. Which is a lot like writing!

"We circle so we might find our footing."

I'm so struck by how this circling pattern shows up in so many ways in our lives—and how it always feels like we're so lost and yet it's the very means for finding our way. And if we let it, it can become the most interesting part of the journey.

I see you in your circling, friend. You're arriving somewhere profound even as you continue to venture into the wild.